Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and the Buddha’s Teaching (1/3)

An introduction to the Buddha and the scriptures.

Hi friend,

It’s amazing that twenty-five centuries ago, an Indian man 🧘🏽♂️ was already teaching the six ACT skills.

In his paper Buddhism and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Steven C. Hayes writes,

The ACT work was always closely connected to issues of spirituality […] and the parallels between ACT and Buddhist thinking are quite clear in some areas. However, there was no conscious attempt to base ACT on Buddhism per se, and my own training in Buddhism was limited. It is for that very reason that these parallels may cast an interesting light on the current discussion. It is one thing to note how Buddhist philosophy and practices can be harnessed to the purposes of behavioral and cognitive therapy. It is another to note how the development of a behavioral clinical approach has ended up dealing with themes that have dominated Buddhist thought for thousands of years. Such an unexpected confluence strengthens the idea that both are engaging topics central to human suffering.

Indeed, the ACT community and the Buddhist community have both been exploring topics central to human suffering, and it is pivotal to our world’s mental health that these two communities engage in conversations, share findings, and enrich each other’s therapeutic endeavors. So far, the vast majority of research papers and videos on ACT and Buddhism has been produced by ACT experts with an enthusiasm for Buddhism, and embarrassingly little by Buddhist teachers with an interest in ACT. For that reason the conversation has been lagging behind in Buddhist scholarship, and I would like to bridge this gap.

I am writing this series of articles for the intelligent ACT practitioner who would like to learn from the Buddha. I will first introduce you to the Buddha and the original scriptures of Buddhism. Then I will give you a comparative overview of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and the Buddha’s teaching. Then I’ll show you how, according to the Buddha, Acceptance and Commitment support each other. After that, I will break down how the Buddha taught each of the six ACT skills; empower you with an ACT-Dhamma dictionary that will allow you to further delve into the original Buddhist scriptures for yourself; and offer you time-tested suggestions of practice.

This is East meets West; tradition meets innovation; spirituality meets science.

The Buddha

We cannot remind ourselves often enough that Buddhism is, first and foremost, the teachings of the Buddha — not the commentaries of Lama X, Ajahn Y, or Zen Master Z 😉 The Buddha was a genius spiritual teacher who lived in Northeast India in the fifth century BC. "Buddha" was not his proper name but an honorific meaning "the awakened one" or "the one who understands". His first name is not clear in the earliest texts1, but his family name was Gotama.

The son of a wealthy ruler2, Gotama left his mansion at the age of twenty-nine to become a wandering ascetic and find a way out of suffering3.

The spiritual scene in India at that time was already bursting with all kinds of masters, sects, philosophical doctrines, and practices. Gotama sought guidance from two renowned, non-Vedic (samaṇa) teachers and quickly mastered their meditation practices4. Concluding that these meditations, while blissful in the moment, did not lead to lasting healing and liberation, Gotama left these teachers and experimented with self-mortification practices — going naked and ignoring conventions, practicing long breath holds, standing or squatting for extended periods, exposing himself to extreme temperatures, tearing out his hair and beard, sleeping on a mat of thorns, sleeping in a charnel ground with the bones of the dead for pillow, eating his own excrement, and consuming extremely limited diets and portion sizes5 6.

After a few years7 of tormenting his body to the extreme, and still not having found the liberation of mind he was looking for, Gotama concluded,

Whatever ascetics and brahmins have experienced painful, sharp, severe, acute feelings due to overexertion — whether in the past, future, or present — this is as far as it goes, no-one has done more than this. But I have not achieved any superhuman distinction in knowledge and vision worthy of the noble ones by this severe, gruelling work. Could there be another path to awakening?

Gotama remembered a pleasant meditative experience he once had as a child sitting at the foot of a rose-apple tree. He reproduced the experience by stabilizing his attention in the present moment, without grasping at anything, and found bliss in that.

Gotama reflected,

Why am I afraid of this pleasure, for it has nothing to do with sensual pleasures or unskillful mental qualities?8

Gotama intuited that the path to healing and liberation must be a middle way (majjhimā paṭipadā) between the sensual pleasures he’d pursued as a prince and the self-mortification he’d practiced as an ascetic; a path filled with soul-nourishing pleasures, namely,

the clear conscience of ethical living (anavajja sukha), and,

the inner bliss of mindful acceptance (jhāna sukha).

Seeing Gotama renounce self-mortification and eat normally again, his five ascetic companions judged him unworthy of their comradeship and abandoned him9.

Alone, his health restored, Gotama could now delve fully into the practice of mindful acceptance.

To keep his mind in the present moment without clinging, Gotama anchored his attention on his natural in- and out-breaths. Once his attention was stably established on his breath, he would spread it to his whole body. Aware of all his physical sensations as they were, not discriminating too much between pleasant and unpleasant sensations, Gotama experienced meditative bliss. Over time, Gotama learned not only to replicate the experience at will, but also to deepen the bliss by increasing psychological acceptance (upekkhā) of all physical sensations. Unafraid of unpleasant sensations and unattached to pleasant sensations, allowing for a perfectly free flow in his body and mind, fully aware and fully accepting, Gotama could now familiarize himself with the Liberating Truth (dhamma) and begin to untie the deepest knots in his nervous system10.

With his awareness open and light, free from conceptualization, Gotama woke up to the fact that everything changes (anicca). In the past, everything changed; in the future, everything will change; and in the present, everything is changing. Whether outside or inside, in obvious or subtle ways, everything is changing. And it is not just that things decide to change themselves — things change according to countless conditions. Changing according to countless conditions, all things are unreliable (dukkha), including Gotama’s body, sensations, thoughts, and consciousness. Since all things are unreliable, all forms of psychological attachment (taṅhā) and identification (ahaṁkāra) are bound to generate friction between mind and reality, and therefore, suffering. Gotama realized that there is no sovereignty (anattā), i.e., no full control, anywhere. The more his mind demanded or expected things to be a particular way, the more it became dissatisfied, entangled, and rigid, and the more his mind embraced the reality of sovereignlessness11, the more it grew fulfilled, free, and flexible.

With the complete psychological integration that “nothing is worth holding onto”12, Gotama fully let go of all clinging, including clinging to consciousness, and experienced an immortal space, without beginning nor end, unconditioned, sublime, peaceful, the highest healing and happiness — the unbinding (nibbāna)13.

The earliest texts do not mention how many days, months, or years elapsed from the moment Gotama had his first taste of unbinding to his final enlightenment. What we do know is that he,

possessed an unflinching resolve14,

practiced breath-based mindfulness15,

cultivated thoughts of contentment and kindness16,

refined his psychological acceptance17,

developed an open, unified, and bright awareness18, and,

contemplated change, the emotional price of attachment, and the bliss of letting go19.

After he had accumulated enough meditative experience, and probably after he had already attained the second and third stages of awakening, one cool evening, near Uruvelā village, in a fragrant grove at hearing distance from the babbling of the Nerañjara river20, Gotama sat under a pipal tree21 hoping to make a final meditative breakthrough.

When the morning broke, Gotama had become a noble one (arahant), a fully awakened person (buddha). He had uprooted all identification and attachment in his psyche, rewired his brain towards complete understanding and acceptance, and found the highest healing and happiness in that22.

The Buddha would later declare,

Any sensual pleasure in the world, and any heavenly bliss, isn’t worth one sixteenth-sixteenth of the bliss of the ending of attachment.23

Gotama was thirty-six when he became a Buddha24. Over the next forty-four years25, he travelled on foot in the Middle Land (majjhima desa), an area which roughly corresponds to today’s states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Wherever he went, the Buddha grew his community of monks, nuns, lay men, and lay women, and taught,

ethical living (sīla),

mindful acceptance (samādhi), and,

liberating wisdom (paññā).

Following his instructions, thousands realized various degrees of awakening.2627

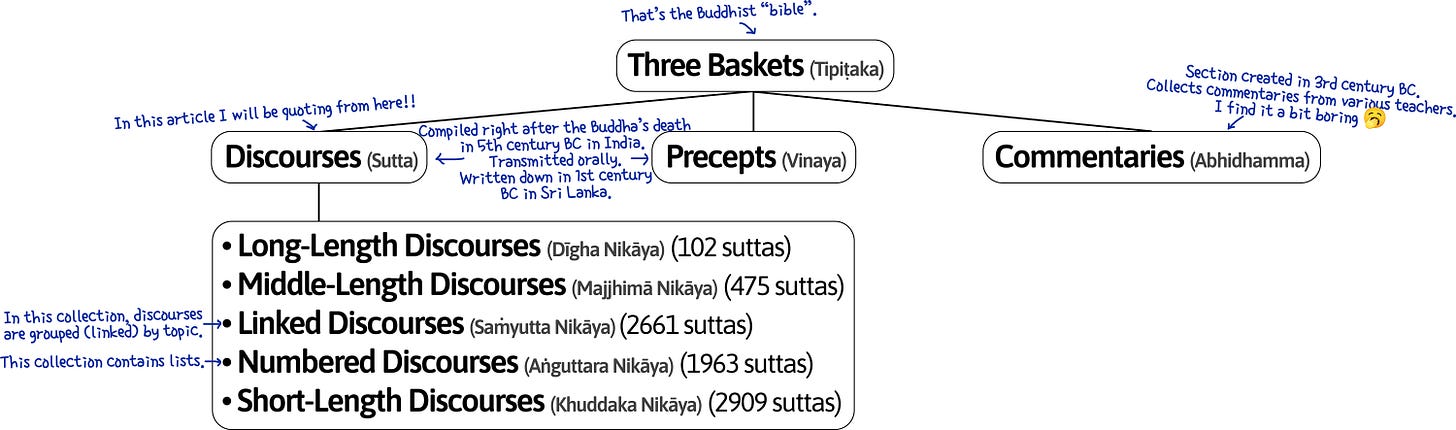

The Scriptures

In this series of articles, I have quoted and will continue to quote from the earliest Buddhist scriptures. If you’re curious to know how these scriptures were organized and transmitted (I think it’s fun, but I’m a Buddhist nerd 🤓), please read on — otherwise, you may like to jump to the next section.

The “Buddhist Bible” is called the “Tipiṭaka”, a Pāḷi word which means “three baskets”. The analogy here is that in the same way that Indian laborers carried baskets over their head and passed these baskets onto fellow laborers’ head, students of the Buddha committed teachings to memory and passed these teachings onto the next generation’s memory.

The intelligent, modern thinker (also known as “you”) will understandably question the authenticity of these teachings, particularly when learning that during their first four centuries, they were only transmitted orally. How can we trust monastics to reliably pass on thousands of teachings for four centuries, when you and I only need four minutes playing telephone28 with our friends to create linguistic catastrophes?

The question of authenticity is as complex as it is fundamental.

The only thing I can guarantee is that studying these discourses is one of the best investments I’ve made in my life. I apply things I learned in them every day and benefit tremendously.

It is worth saying that I don’t believe all of these suttas contain the unerringly verbatim words of the Buddha. That would be unrealistic and unnecessary. On the contrary, we should expect conscientious monastics to slightly and thoughtfully edit and arrange the Buddha’s words to facilitate memorization and comprehension29.

That said, I do believe that the suttas contain, by and large, faithful accounts of what the Buddha taught, and that the transmission was made reliable by four factors:

📦 An excellent packaging

One of our world’s most influential teachers, the Buddha knew how to present information in clear and memorable ways. Among the pedagogical devices he used were:

gradual instructions — by describing the path in details, from a complete beginner’s standpoint to full enlightenment, each student could see where they were and what next step to take toward liberation30,

lists — think the four noble truths, the noble eightfold path,..., well-organized lists are wonderfully neuroergonomic31,

metaphors — vivid analogies brought his points to life and aided retention32,

creative repetition — he explained the same subjects, over and over, from many, slightly different angles33,

synonyms — ranges of synonyms for key concepts ensured at least one word clicked with every listener34,

summaries — prose or verse summaries underlay key takeaways35,

socratic questioning — incisive, open questions helped his audience see the Liberating Truth for themselves36,

humor — his deadpan, witty jokes are often degraded by criminally boring translators, but the Buddha was indeed a funny dude37, and,

props — objects or situations served to illustrate his points38.

💛 The love of a community

When we love something, we give it our time and attention. At the time of the Buddha, thousands of men and women loved his teaching so much that they left family, friends and possessions behind to devote all of their time to study and practice it39. The sense one gets from reading the discourses (suttas) and monastic code (vinaya) is that these monks and nuns were deeply human40, came from all layers of society41, and showed a wide range of aptitudes for walking the spiritual path42. Thousands of lay men and lay women also saw the Buddha as their spiritual guide43, and practiced his teaching on ethical and mindful living with varying degrees of commitment and success.

These students loved their teacher’s disdain for superstition44 and secrecy45, and his respect for free inquiry46 and experiential verifiability47. The Buddha praised intelligent questions48 and encouraged students to “cross-question one another about [his teaching] and dissect it: ‘How is this? What is the meaning of this?’”49. Acquiring mere knowledge of his teaching (sutamayā paññā) wasn’t enough; one also had to intellectually understand it (cintāmayā paññā); and then put it into practice to awaken to a direct understanding of the Liberating Truth (bhāvanāmayā paññā)50. Because of this, students of the Buddha adopted his teaching deep into their hearts.

Whether monastic or lay, most disciples of the Buddha agreed that the practice is not easy51 but well worth it. Particularly, students who attained spiritual realizations corroborated the Buddha’s claim that such realizations indeed bring the highest healing and happiness52, and these holy women and men played crucial roles in disseminating his teachings.

After training his first sixty disciples to full awakening, the Buddha asked them to,

Go forth for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world […]. Let no two of you go in the same direction. Teach the Liberating Truth which is beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle and beautiful at the end.53

Although the Buddha spurned fame54, his monastic community grew fast55. And while he criticized students who took teaching roles without being liberated themselves56, and affirmed that teaching was not easy, he also encouraged his realized disciples to teach — out of love, gradually, and not for material gain57:

Mendicants, those who you have sympathy for […] — friends and colleagues, relatives and family — should be encouraged, supported, and established in the true comprehension of the four noble truths.58

Teaching was seen as an act of kindness59, and the Liberating Truth as a gift (dhammadāna) more precious than material gifts (āmisadāna)60. Hence, many monastics taught — whether to large audiences61, to groups of twenty to forty mentees62, in one-on-one consultations63, or when stopped informally during their daily almsround64. Many lay practitioners also taught — whether to other lay people65, ascetics of other religions66, or Buddhist monastics67. And countless students of the Buddha, while unable to expound the teaching in detail, shared the little they knew68 and encouraged family and friends to go hear the Buddha69 or one of his eminent disciples70 speak.

🤓 A culture of memorization

Writing might have already been in use in the 5th century BC in Northeast India71 — but even if it had, it was only used by a tiny minority. The vast majority was illiterate, and relied on listening and memorizing for their learning. Without the assistance of devices or notes, I think it’s safe to assume that these people’s memories were better trained than ours. The brahmins72 had developed highly efficient systems to memorize and transmit their “vedas” . The samaṇas73 who taught Gotama at the beginning of his spiritual quest also required students to memorize their teachings. And after his awakening, Gotama too promoted a culture of memorization in his community:

[…] these four competent, educated, assured, learned people — who have memorized the teachings and practice in line with the teachings — beautify the community. What four? A monk, a nun, a layman, and a laywoman.74

Before giving a talk, the Buddha made sure the atmosphere was one of safety and respect75. Then, he would typically announce the topic of his talk, and ask his listeners to pay attention76. At times, he would also explicitly ask listeners to memorize the teaching they were about to hear77 or had just heard78.

The Buddha encouraged students to meet his awakened disciples, listen to their teachings attentively, and remember them79. It was also typical for these eminent disciples, after answering a question, to invite their audience to ask the Buddha the same question and remember his answer80. At times, a powerful and busy individual, such as a king81 or a queen82, sent a subordinate to visit the Buddha on their behalf, pay their respects, ask him a question, remember his answer, and report it to them.

The Buddha regularly tested his students’ knowledge and understanding. When students remembered a teaching correctly, he praised them83. When they showed incomplete understanding, he completed it for them84. When they did not know, they themselves asked, “[…] may the Buddha himself please clarify the meaning of this. [We] will listen and remember it”85. And in the rare case a student obstinately misunderstood and misrepresented his teaching… the Buddha invited the individual to a barbecue party 🍡 — without telling him he was the one about to get roasted 🔥86

The Buddha saw erudition (and not biological age) as one of the qualities that make one an “elder”87. Among his erudite disciples was Ānanda88, who not only recited teachings for others to listen89, but also described the qualities that make one erudite90 and gave his fellow monastics advice on how to hear, memorize, and understand new teachings91.

Again and again, the Buddha reminded his students of the dangers of misremembering his teachings and the benefits of remembering his teachings correctly — not only for themselves92 but, very importantly, for future generations93.

👥 Group recitations

Like other religious leaders of his time94, the Buddha instructed his disciples to meet regularly to recite his teachings. To ensure faithful transmission, he entrusted erudite students with the task of initiating group recitations:

[…] the mendicants who are very learned — inheritors of the heritage, who have memorized the teachings, the monastic law, and the outlines — [should] carefully make others recite the discourses.95

One of the advantages of group recitation (saṅgīti) was that it allowed individuals to self-correct if they didn't remember a passage correctly:

[…] you should all come together and recite in concert, without disputing, those things I have taught you from my direct knowledge, comparing meaning with meaning and phrasing with phrasing, so that this spiritual path may last for a long time.96

The Buddha also encouraged his monastics to be careful when considering any new information about his teaching. If this new information did not agree with what was already well established, one should discard it; if it did agree, one should be remember it; and so, regardless of who made the claim97.

Toward the end of the Buddha’s life, Sāriputta, one of his most prominent disciples, emphasized the importance of group recitations to preserve the Buddha’s teachings, and proposed a first way of organizing his teachings, by numerical order, to facilitate memorization. The Buddha approved98.

Soon after the Buddha's death, Mahākassapa, another prominent disciple of the Buddha, made a formal proposal to the monastic community: five hundred fully realized monks would gather in the city of Rājagaha for three months to recite, organize, and crystallize the Buddha's teachings into a well-structured canon that would facilitate recitation and transmission. The community accepted Mahākassapa's proposal, and the event, known to historians as the First Buddhist Council, unfolded successfully99.

Around 300 BCE, a Second Buddhist Council was held in Vesālī to settle disputes over minor points of the monastic code.

Around 250 BCE, a Third Buddhist Council was held at Pāṭaliputta to add a third section (piṭaka) of commentaries.

Around 100 BCE, a Fourth Council was held in Sri Lanka to formally write down the Tipiṭaka for future generations100.

For our purposes, dear reader, I don’t need you to believe that the Buddha was a historical figure, or that these scriptures are authentic. I just need you to open your mind wide enough to seriously consider what these scriptures have to say 🙂

(PS: Pheeeewwwww…. that was a long piece to write….. there’s more coming… but please be patient 😊)

With so many honorifics attributed to the Buddha, and in what seems like a culture which deemed too informal to use a holy person’s given name, it is surprisingly hard to find the Buddha’s first name in the earliest scriptures. The name “Siddhattha” in reference to the Buddha does not appear even once in the earliest texts — only in the jātakas and later commentaries, and even then, it seems to be proposed as another epiteth meaning “one who has accomplished his task”. Based on the earliest texts, his first name may have been “Aṅgīrasa” (DN32, SN8.11, SN3.12, AN5.195, Thag10.1, Thag21.1), but Aṅgīrasa could also have been just another epithet meaning “emitting rays from the limbs”, i.e. “luminous”. The jury is still out, and my Pāḷi is unfortunately not good enough for me to form an opinion. Since I prefer to adhere to what shines clear in the earliest scriptures, in this article I will refer to the Buddha prior to his enlightenment by his last name, “Gotama”.

The Shakya chiefdom over which Gotama’s father, Suddhodana, ruled, was vassal to the Kosala kingdom: ”King Pasenadi of Kosala knows that the ascetic Gotama has gone forth from the neighboring clan of the Sakyans. And the Sakyans are his vassals. The Sakyans show deference to King Pasenadi by bowing down, rising up, greeting him with joined palms, and observing proper etiquette for him.” DN27. This is why in MN89, King Pasenadi says, “The Buddha is Kosalan, and so am I". In all of the suttas, Suddhodana is only mentioned once as a “king” (rājā), in DN14.

The Buddha describes his upbringing: "My lifestyle was […] extremely delicate. In my father’s home, lotus ponds were made just for me. […] I only used sandalwood from Kāsi, and my turbans, jackets, sarongs, and upper robes also came from Kāsi. And a white parasol was held over me night and day, with the thought: ‘Don’t let cold, heat, grass, dust, or damp bother him.’ I had three stilt longhouses—one for the winter, one for the summer, and one for the rainy season. I stayed in a stilt longhouse without coming downstairs for the four months of the rainy season, where I was entertained by musicians—none of them men. While the bond servants, workers, and staff in other houses are given rough gruel with pickles to eat, in my father’s home they are given fine rice with meat.” AN3.39. “I used to amuse myself, supplied and provided with sights [,] sounds [,] smells [,] tastes [and] touches […] that are […] agreeable, pleasant, sensual, and arousing.” MN75. “[…] before my awakening […] I too, being liable to be reborn, sought what is also liable to be reborn. Myself liable to grow old, fall sick, die, sorrow, and become corrupted, I sought what is also liable to these things. Then it occurred to me: ‘Why do I, being liable to be reborn, grow old, fall sick, sorrow, die, and become corrupted, seek things that have the same nature? Why don’t I seek the unborn, unaging, unailing, undying, sorrowless, uncorrupted supreme sanctuary from the yoke, unbinding?’” MN26. “I was twenty-nine years of age […] when I went forth to discover what is skillful.” DN16. “[…] while still black-haired, blessed with youth, in the prime of life—though my mother and father wished otherwise, weeping with tearful faces—I shaved off my hair and beard, dressed in ocher robes, and went forth from the lay life to homelessness.” MN26, MN85, MN95, MN100.

Proponents of self-mortification claimed that such practices would purify one from accumulated bad karma (e.g. “[…] those Jain ascetics said to me, ‘Reverend, the Jain ascetic of the Ñātika clan […] says, “O Jain ascetics, you have done bad deeds in a past life. Wear them away with these severe and grueling austerities. And when in the present you are restrained in body, speech, and mind, you’re not doing any bad deeds for the future. So, due to eliminating past deeds by fervent mortification, and not doing any new deeds, there’s nothing to come up in the future. With no future consequence, deeds end. With the ending of deeds, suffering ends.”” MN14) and build up a spiritual fire (tapas) within that would grant them power.

“Now at that time the five mendicants were attending on me, thinking, ‘The ascetic Gotama will tell us of any truth that he realizes.’ But when I ate some solid food, they left disappointed in me, saying, ‘The ascetic Gotama has become indulgent; he has strayed from the struggle and returned to indulgence.’” MN36, MN85, MN100.

In this paragraph I describe the first twelve steps of breath-based mindfulness (e.g. SN54.8), which are, according to my research, another description of jhāna practice (this is why, for instance, in the introduction of MN118 the Buddha does not mention monks who practice jhāna). In both jhāna descriptions such as those found in DN2 and the first twelve steps of breath-based mindfulness, we are invited to establish full body awareness, progress from joy to equanimity, and free our mind from the five obstacles (desire, aversion, agitation, somnolence, doubt). This is the best platform from which to practice vipassanā.

Absence of sovereignty, absence of full control. (Yeah, it’s not in the dictionary — yet — I know 😉)

Explanations in my article Ultra-Condensed Vipassanā.

“Mendicants, I have learned these two things for myself—to never be content with skillful qualities, and to never stop trying. I never stopped trying, thinking: ‘Gladly, let only skin, sinews, and bones remain! Let the flesh and blood waste away in my body! I will not stop trying until I have achieved what is possible by human strength, energy, and vigor.’ It was by diligence that I achieved awakening, and by diligence that I achieved the supreme sanctuary from the yoke.” AN2.1. But also worth mentioning is the Buddha taught that spiritual practice without wisdom is like trying to milk a cow by the horns 😂 MN136.

“That’s how breath-based mindfulness, when developed and cultivated, is very fruitful and beneficial. Before my awakening —when I was still unawakened but intent on awakening — I too usually practiced this kind of meditation.” SN54.8.

Ficus religiosa, also called peepul, or Bodhi tree. Here I go with the traditional account, as asserted in DN14, although this sutta also describes the “thirty-two marks of the great man” which seems like a later addition. In the seven days after his awakening, the Buddha stayed in the same grove and spent most of his time in sitting meditation, but he also needed to relieve himself and most probably eat and drink, which could justify the variations between Ud1.1 (bodhi tree), Ud1.2 (bodhi tree), Ud1.3 (bodhi tree), Ud1.4 (goatherds’ banyan tree), Ud2.1 (mucalinda tree), SN47.18 (goatherds’ banyan tree), AN4.21 (goatherds’ banyan tree), and AN4.22 (goatherds’ banyan tree). SN4.24 (goatherds’ banyan tree) contains chronological discrepancies and it is not clear whether it refers to Gotama before or after awakening.

None of the earliest texts explicitly states Gotama’s age when getting enlightened. However, we know from DN16 that he left home at age 29. Snp3.2 and SN4.24 describe him meditating in Uruvelā when Māra, the personification of temptation, is said to “have been following Gotama for seven years” trying to discourage him from his quest. Although SN4.24 contains chronological discrepancies, it still seems reasonable to me to assume that these seven years describe the period between the moment Gotama left home and the crucial moment he was on the brink of enlightenment. This would mean Gotama became a Buddha at age (29+7=)36. The early texts do not indicate exactly how long each of the three periods of Gotama’s quest lasted. The only thing we know from MN12 is that he practiced asceticism for “several years” (nekavassa) — “Such was my coarseness, Sāriputta, that just as the bole of a tindukā tree, accumulating over the years, cakes and flakes off, so too, dust and dirt, accumulating over the years, caked off my body and flaked off.” It seems unlikely to me that Gotama mastered the āruppasamāpattī and was offered teaching positions in less than a year, or went from remembering jhāna to full enlightenment in less than a year. Therefore I imagine the timeline of Gotama’s quest looked something like this: learns the āruppasamāpattī ≈ two years; practices asceticism ≈ three years; practices the middle way ≈ two years.

To learn more about the Buddha’s life according to early Buddhist texts, I highly recommend Footprints in the Dust by Ven. Shravasti Dhammika.

Aka Chinese Whispers, for my readers in the UK.

Here I am not implying that the Buddha needed his disciples to help him clarify his message. But for example, at the beginning of his conversations were polite formalities which did not convey his teachings and would therefore best be summarized or edited out. Or, when noticing that the Buddha gave the same talk in two different locations, save a few unimportant choice of words, monastics would better memorize the same text since no doctrinal content would be lost. Or, when the Buddha used one word that was specific to the particular region he was teaching in, he needed his disciples to add synonyms in other dialects before freezing his teachings in the SuttaPiṭaka, so that people from other regions would also understand.

E.g. AN8.11 “If the Realized One bowed down or rose up or offered a seat to anyone, their head would explode!” 😂

The monastic code (vinaya) is full of stories of monks and nuns doing crap 🤦♂️

E.g. “Just as, when the great rivers […] reach the great ocean, they give up their former names and designations and are simply called the great ocean, so too, when members of the four social classes—khattiyas, brahmins, vessas, and suddas—go forth from the household life into homelessness in the Dhamma and discipline proclaimed by the Tathāgata, they give up their former names and clans and are simply called ascetics following the Sakyan son.” AN8.19.

The Buddha forbade his disciples from making sacrifices to the gods, invoking the goddess of luck, foretelling the future, reciting charms, and other similar practices he considered “wrong means of livelihood” and “debased arts”. E.g. DN1. One time, while giving a Dhamma talk, the Buddha sneezed. Many monks, as was the custom at that time, exclaimed loudly, “Live long!” disturbing the peace and interrupting the talk. The Buddha asked, “Can your wishes affect someone’s life expectancy?” to which the monks replied “no”. The Buddha then forbade his students from participating in this custom, and resumed his talk. pi-tv-kd15. Another time, when asked what he considered to be “the most auspicious signs” (maṅgalamuttamaṃ), the Buddha described a number of ethical guidelines and mindfulness practices that culminate in psychological liberation, before concluding, “These are the most auspicious signs.” Snp2.4. Although the Buddha cautiously acknowledged the possibility of developing psychic powers such as clairvoyance and clairaudience (e.g. AN8.64), he also said, “seeing the danger of such miracles, I dislike, reject and despise them”. To him, the best miracle was “the miracle of instruction”, i.e. the ability to teach others how they can liberate themselves from suffering. E.g. DN11. While orthodox Brahmins proclaimed to be “the best cast”, the Buddha said people should be judged only on the strength of their character (e.g. MN96); and while Brahmins believed to be “born out of Brahma’s mouth“ the Buddha reminded them they were born out of their mothers’ womb just like everyone else 😅 E.g. MN93.

“Three things shine in the open, not undercover. What three? The moon shines in the open, not under cover. The sun shines in the open, not under cover. The teaching and training proclaimed by a Realized One shine in the open, not under cover.” AN3.131. ”I’ve taught the Dhamma without making any distinction between secret and public teachings. The Realized One doesn’t have the closed fist of a teacher when it comes to the teachings.” DN16, SN47.9.

E.g. countless times such as in SN12.41, the Buddha described his teaching as “ehipassiko”, “that which [is open for everyone to] come [and] see”.

The Buddha said his teaching was “paccattaṃ veditabbo viññūhi”, “to be personally experienced by the wise”. E.g. SN16.3.

For monastics, the main difficulties involved celibacy, community living, and training oneself. For lay practitioners, the main difficulties involved resisting the temptations and distractions of the world, and making time for studies and practice.

E.g. the enlightened nun Saṃghā who composed the poem, “Having given up my home, my child, my cattle, and all that I love, I became a nun. Having given up desire and hate, having dispelled ignorance, and having plucked out attachment, root and all, I am calmed and emancipated.” Thig1.18.

E.g. One time the Buddha was travelling with a large group of monastics when he reached a village called Icchānaṅgala. The brahmins there heard about him and came towards where he was staying, making great noise. The Buddha asked his attendant, “- Nāgita, who’s making that dreadful racket? You’d think it was fishermen hauling in a catch! - Sir, it’s these brahmins and householders of Icchānaṅgala. They’ve brought many fresh and cooked foods, and they’re standing outside the gates wanting to offer it specially to the Buddha and the mendicant Saṅgha. - Nāgita, may I never become famous. May fame not come to me. [The Buddha totally failed at that one 😆] There are those who can’t get the bliss of renunciation, the bliss of seclusion, the bliss of peace, the bliss of awakening when they want, without trouble or difficulty like I can. Let them enjoy the filthy, lazy pleasure of possessions, honor, and popularity.” AN5.30. The Buddha taught his monastics, “Bhikkhus, this holy life is not lived for the sake of deceiving people, for the sake of cajoling people, for the sake of profiting in gain, honour, and fame, nor with the idea, ‘Let people know me thus.’ This holy life, bhikkhus, is lived for the sake of direct knowledge and full understanding.” E.g. Iti36. In SN17.5 the Buddha compares a monk who is proud of his great fame to a dung beetle who is proud of his huge pile of dung. However, the Buddha also taught his lay disciples how to improve their reputation by living ethically. E.g. AN5.34.

Eg. pli-tv-kd1.

E.g. “Whatever should be done, mendicants, by a compassionate teacher out of compassion for his disciples, desiring their welfare, that I have done for you.” SN35.146.

E.g. Rohinī explains to her dad what she loves about the ethical training of monastics in Thig13.2.

E.g. the lay disciple Anāthapiṇḍika explains the harms of being attached to one’s view to a group of ascetics in AN10.93.

E.g. “At one time the Buddha was wandering in the land of the Kosalans together with a large Saṅgha of mendicants when he arrived at a village of the Kosalan brahmins named Venāgapura. The brahmins and householders of Venāgapura heard: “It seems the ascetic Gotama—a Sakyan, gone forth from a Sakyan family—has arrived at Venāgapura. He has this good reputation: ‘That Blessed One is perfected, a fully awakened Buddha, accomplished in knowledge and conduct, holy, knower of the world, supreme guide for those who wish to train, teacher of gods and humans, awakened, blessed.’ He has realized with his own insight this world […] and he makes it known to others. He teaches the Liberating Truth that’s good in the beginning, good in the middle, and good in the end, meaningful and well-phrased. And he reveals a spiritual practice that’s entirely full and pure. It’s good to see such perfected ones.”” AN3.63.

E.g. “Now a good report concerning this revered lady has spread about thus: ‘She is wise, competent, intelligent, learned, a splendid speaker, ingenious.’ Let your majesty visit her.” SN44.1.

Ud3.9 suggests it was. See “lekhā” (an inscription, but literally a scratch), “likhati” (to write), “lekhāsippaṃ” (the writing craft), and “lekhaka” (a scribe).

Hereditary priests of traditional Vedic religion.

Wandering ascetics who rejected the Vedic rituals and caste structure.

For instance, in DN3 the Buddha remarks to a Brahmin that it is improper for him to speak standing while he was sitting. In DN4, the Buddha asked a group of brahmins not to speak all at the same time but to choose their most learned representative to engage in conversation. In the sekhiya rules 57 to 72, the Buddha forbids his monks to teach to someone holding a staff, a knife, a weapon, or a sunshade; wearing shoes, sandals, or a headdress; lying down, clasping their knees, sitting on a higher seat, sitting in a vehicle, standing, or walking, unless for health reasons.

“There the Buddha addressed the mendicants, “Mendicants!” “Venerable sir,” they replied. The Buddha said this: “Mendicants, I shall teach you [about this topic]. Listen and apply your mind well, I will speak.”” E.g. MN149.

E.g. “Listen to me, monks, I will teach you the cleansing, Liberating Truth. All of you remember it.” Snp2.14.

E.g. “Monk, did you hear that exposition of the teaching? Learn that exposition of the teaching, memorize it, and remember it.” SN35.113.

E.g. Ānanda, after expounding his understanding of a brief statement of the Buddha: “Now, friends, if you wish, go to the Blessed One and ask him about the meaning of this. As the Blessed One explains it to you, so you should remember it.” SN35.116.

E.g. “And then King Ajātasattu addressed Vassakāra the brahmin minister of Magadha, “Please, brahmin, go to the Buddha, and in my name bow with your head to his feet. Ask him if he is healthy and well, nimble, strong, and living comfortably. And then say: […] Remember well how the Buddha answers and tell it to me. For Realized Ones say nothing that is not so.”” DN16.

E.g “Then Queen Mallikā addressed the brahmin Nāḷijaṅgha, “Please, brahmin, go to the Buddha, and in my name bow with your head to his feet. Ask him if he is healthy and well, nimble, strong, and living comfortably. And then say: ‘Sir, did the Buddha make this statement: “Our loved ones are a source of sorrow, lamentation, pain, sadness, and distress”?’ Remember well how the Buddha answers and tell it to me. For Realized Ones say nothing that is not so.”” MN87.

E.g. ““Monks, do you remember the Four Noble Truths taught by me?” When this was said, a certain monk said to the Buddha: “Venerable sir, I remember the Four Noble Truths taught by you.” “But how, monk, do you remember the Four Noble Truths taught by me?” [Monk answers.] “Good, good, monk! It is good that you remember the Four Noble Truths taught by me.”” SN56.15.

E.g. One time, monks could not help their brother Ariṭṭha to let go of a grave misconception he had about the Buddha’s teachings. “Then the Blessed One addressed a certain bhikkhu thus: “Come, bhikkhu, tell the bhikkhu Ariṭṭha […] in my name that the Teacher calls him.” […] The Blessed One then asked him: “Ariṭṭha, is it true that the following pernicious view has arisen in you: […] “Exactly so, venerable sir. […]” “Misguided man, to whom have you ever known me to teach the Dhamma in that way?” […] “Bhikkhus, what do you think? Has this bhikkhu Ariṭṭha […] kindled even a spark of wisdom in this Dhamma and Discipline?” […] Then the Blessed One addressed the bhikkhus thus: “Bhikkhus, do you understand the Dhamma taught by me as this bhikkhu Ariṭṭha […] does when by his wrong grasp he misrepresents us, injures himself and stores up much demerit?” MN22. The Buddha could be kind, even motherly, to his students who wanted to train. E.g. “Rejoice, Tissa, rejoice! I’m here to advise you, to support you, and to teach you.” SN22.84. But when necessary, he could also speak harshly if he believed it to be more conducive to the other person’s long term happiness, as explained in MN58. In this way, the Buddha was like a horse trainer who used gentler or harsher methods depending on the horse he was training. AN4.111. But the Buddha never used physical punishment as a way to teach disciples. The worst form of punishment, in the Buddha’s teachings, was silence (”[…] give the divine punishment to the mendicant Channa.” “But sir, what is the divine punishment?” “Channa may say what he likes, but the mendicants should not correct, advise, or instruct him.” DN16), or, much more commonly, expulsion from the monastic order.

E.g. “There are these four qualities that make a senior. […] They’re very learned, remembering and keeping what they’ve learned. These teachings are good in the beginning, good in the middle, and good in the end, meaningful and well-phrased, describing a spiritual practice that’s entirely full and pure. They are very learned in such teachings, remembering them, reinforcing them by recitation, mentally scrutinizing them, and comprehending them theoretically.” AN4.22.

“And he selected Ānanda also for the one in the five hundred less one spending the rains in chanting dhamma and discipline in the best of resorts.” pli-tv-kd21.

E.g. MN22, MN53, MN70, DN33, DN34, AN3.30, AN4.6, AN4.21, AN4.52, AN4.97, AN4.186, AN4.191, AN5.26, AN5.47, AN5.74, AN5.87, AN5.96, AN7.5, AN7.6, AN7.7, AN7.61, AN7.62, AN7.67, AN7.68, AN8.2, AN8.57, AN8.58, AN9.19, AN10.17, AN10.18, AN10.50, AN10.55, AN10.68, AN10.82, AN10.97, AN10.98, AN11.14, AN11.17.

Eg., in brahmin communities: “Now at that time the brahmin Sela was residing in Āpaṇa. He had mastered the three Vedas, together with their vocabularies and ritual performance, their phonology and word classification, and the testaments as fifth. He knew them word-by-word, and their grammar. He was well versed in cosmology and the marks of a great man. And he was teaching three hundred young students to recite the hymns.” MN92 “You teach the tutors of many, and teach three hundred young students to recite the hymns.” MN95. When speaking of the samanas that Gotama first studied under, he said, “I quickly memorized that teaching. As far as lip-recital and verbal repetition went, I spoke the doctrine of knowledge, the elder doctrine.” MN26, MN36, MN85, MN100. Even though these passages do not explicitly mention group recitals in samana communities, it seems logical that they would adopt the time-tested practices of transmission of the brahmins.

DN29. Imagine that a group of 20 monks recited a teaching, with 1 of them remembering one way, and 19 remembering another way. It would be statistically nearly impossible that this 1 monk remembered the teaching correctly while the 19 other monks remembered it incorrectly in the same way. (Interestingly, this decentralized, consensus-driven way of maintaining information is a core feature of blockchain technology.)

This is known as the teaching on the “four main references” (cattāro mahāpadesa) and is found in AN4.180 and DN16. The “four main references” are when a monk reports having heard that “this is the teaching of the Buddha” 1. directly from the Buddha, 2. from a whole community with learned elders, 3. from many learned elders, or 4. from a single learned elder. In all cases, the recommended response was the same: to compare this information to what is well-known about the Buddha’s teaching. If it didn’t fit, it should discarded; if it did fit, it should be remembered.

For a deep dive into the topic of authenticity: The Authenticity of the Early Buddhist Texts, by Bhikkhu Sujato and Bhikkhu Brahmali.

A long read and I will need to go over it a few times. So interesting though. Thank you 💕