Hi friend,

In my previous article, I explained how I created the Arms Swinging exercise I teach. Because it has no exact equivalent anywhere, and because the Daily Wellness Empowerment Program is still in its infancy, I don’t have much scientific research to share with you yet. I apologize for this and hope to be able to fill this gap soon!

Until then, I think it’s safe to assume that my Arms Swinging shares many benefits and mechanisms of action with its closest sibling Ping Shuai Gong, as well as the larger family of Qi Gong exercises from which they stem, and that it is relevant for me to include information about them in this article. We will explore them from three different angles: modern scientific research, Traditional Chinese Medicine theory, and the testimonials of practitioners.

My Arms Swinging

Since I started my morning Hindu Squats and Hindu Pushups routine and evening Arms Swinging routine a few years ago, my body has never felt this strong, flexible, loose, and pain-free. Previous shoulder, lower back, and knee pains are all gone, although the knee pain (an old skateboard injury) can come back a bit if I sit in meditation for over an hour. Doing the Arms Swinging exercise before bed never fails to release the tensions accumulated during the day, to leave my body buzzing with peace and relaxation, and to help me sleep more soundly.

Friends also routinely report that the Arms Swinging exercise helps them feel better, sleep better, and relieve all kinds of pain in their shoulders, trapezes, back, and legs. The benefits are sometimes emotional, like one friend reporting that the Arms Swinging exercise had finally brought pleasant sensations back into his body after a long period of feeling disconnected, and another reporting being able to process a deep trauma and make peace with a difficult issue she was facing. You can listen to more testimonials on the DWEP Testimonials playlist.

Apart from this anecdotal evidence, I have only conducted a preliminary survey on my Arms Swinging with brothers and lay practitioners in the monastery, in September 2021. The principle was simple: practice ten minutes of my Arms Swinging exercise, every evening for a week, and then report on how it felt. Twenty people participated.

The results:

Participants gave the Arms Swinging exercise an average score of 4.1/5 for usefulness.

90% of participants said they were likely or very likely to practice it again.

85% of participants said they were likely or very likely to recommend it to a friend.

Typical benefits reported included:

relaxation (74%),

improved breathing (75%),

reduction or disappearance of pain (40% of total — I forgot to ask who had pain to begin with), and

improved sleep (60% self-reported, although I forgot to ask in the questionnaire).

The details of this survey are here.

I find the results extremely encouraging, especially when you consider that this is a DIY, free, simple, and ten-minute long intervention.

The sample size in this study was small (n=20), and although I encouraged participants to be truthful and accurate about their experiences, I kept wondering in the back of my mind if someone was just trying to “be nice”, if I was missing important confounding factors, and how I could improve my protocol and questionnaire. If you have experience in scientific research, I would appreciate it if you could coach me on how to design a better survey next time.

It would be even better if a group of researchers could collaborate with me: you design the methodology, I teach the Arms Swinging, and you collect and analyze the data.

If you’re interested, please contact me.

I will suggest possible mechanisms of action for the Arms Swinging later in this article.

Ping Shuai Gong

According to the Ping Shuai Gong booklet, written by instructors at the Mei Men Qi Gong Center in Taiwan:

More than one hundred thousand people have started practicing it all over the world. The feedback is wonderful. A cranial neurosurgeon had his cancer cured. A woman who almost became blind due to diabetes regained her eyesight. A man who suffered from many years of insomnia now sleeps like a baby. Several cases of depression were also cured. Strokes, high blood pressure, heart diseases, cirrhosis, ulcers, menopause, prostate cancer… The stories are too many to enumerate.

Let’s mention two:

In 1997, when he was 72 years old, Mr. Weihua Yao's health deteriorated rapidly. Within three weeks, he lost 30 pounds and experienced severe pain in his thighs and lower back. The doctor diagnosed him with terminal prostate cancer, which had spread to his bone marrow and was inoperable. The doctor said he had two months to live. After meeting Li Feng Shan (the qigong master who created Ping Shuai Gong - see previous article), he switched to a vegetarian diet and began practicing Ping Shuai Gong every day. For the next three months, he showed signs of detoxification: the backs of his hands turned black, and his body emitted an unpleasant odor. But gradually he regained his weight and strength, the foul odor disappeared, and the hospital tests showed that his antigen level returned to normal. He now recommends Ping Shuai Gong to people.

Mrs. Jingfeng Lan is a trained medical professional who worked in the intensive care unit for many years. Her second daughter, Yunchung, was born frail and developed bronchitis, pneumonia and asthma. She was given the maximum dose of steroids, but her condition only got worse. Mrs. Lan took her daughter to learn Ping Shuai Gong. Since then, her visits to the doctor have been reduced from once a month to once every six months. She still had asthma attacks, but she was able to manage them without medication. Seeing the good results of her second daughter, Mrs. Lan also started Ping Shuai Gong and taught her first daughter, and they also benefited. Mrs. Lan now helps parents to teach their children Ping Shuai Gong.

There are other testimonials on their YouTube channel.

Testimonials are important, but they provide only a weak form of "evidence" known as "anecdotal evidence" and have two limitations:

Even if all reported events were true (someone is sick, practices Arms Swinging, then recovers), there may be no causal relationship between them.

Even if a causal relationship is established with some degree of confidence, the person's experience may not be representative of the experience of most people.

To get a more representative assessment of what an intervention can do for people, it is useful to conduct proper scientific studies.

I have found five studies on Ping Shuai Gong:

#1: Effects of Ping-Shuai-Gong and Arm-Swing-Exercise

In this study, completed in April 2022, 40 participants, aged 60 years and older, were divided into two groups: a Ping Shuai Gong group and a Arm-Swing (another arms swinging variation similar to dịch cân kinh, see previous article) group. Each group practiced for at least 30 minutes, at least 3 times a week, for 3 months. Before and after the intervention, the researchers measured the participants’

cardiovascular fitness — heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure, low frequency oscillations of the microvascular system,

brain activity — changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentrations measured by NIR to assess activity of motor-related cortex activity, and

balance.

Unfortunately, the results of this study are not available online 😢. I have contacted the lead researcher and his hospital, but they haven’t gotten back to me yet. I will update this article as soon as I have the information.

#2: Ping Shuai Gong and Brain Activity

At the Annual Convention of the International Association of Counselors and Therapists (IACT) in Taiwan, Professor Chang reported that during the practice of Ping Shuai Gong, alpha waves are gradually activated in the practitioner. Alpha waves are associated with a meditative state, a reduction in depressive symptoms, and an increase in creative thinking.

#3: Ping Shuai Gong on Perimenopausal Symptoms

A Taiwanese university studied 70 perimenopausal women: half of them were the control group and the other half practiced Ping Shuai Gong for 30 minutes a day for twelve weeks. After six weeks, the women in the intervention group reported significant improvements in menopausal symptoms and sleep quality, and after twelve weeks they were even better off, with a correlation between the level of commitment to the exercise and the improvement in symptoms.

#4: Ping Shuai Gong and Energetic Field

This quirky little study looked at the "aura" of a 70-year-old woman before and after she practiced 10 minutes of Ping Shuai Gong, using a device called the Power AVS (Aura Video Station 7 System). The authors concluded: "10 minutes of PSG practice can increase the range of the aura field and enhance chakra’s energy." I looked up the tool they used and can't decide if it's scammy or legit. If you have any idea, don't hesitate to drop me a line.

#5: Ping Shuai Gong, Shiang Gong, and Therapeutic Sounds on the Cognition, Mood and Sleep of the Elderly

In this study, also conducted by Taiwanese researchers, participants committed to 1-3 sessions per week, each session lasting 30-60 minutes and consisting of a combination of Ping Shuai Gong, another form of qi gong named Shiang Gong, and medical resonance music. Participants showed improvements in cognition, mood and sleep quality, but the other qi gong and sound therapy confound the results, which is why I present this study last.

According to the Ping Shuai Gong booklet,

Traditional Chinese medicine believes that all illnesses result from the blocking of qi. They key to long-term health therefore lies in enhancing the free circulation of qi to increase stability and peacefulness of mind. […] The most effective cures always observe a simple fundamental principle: improving qi and blood circulation to enhance immunity and fortify your body’s own self-defense.

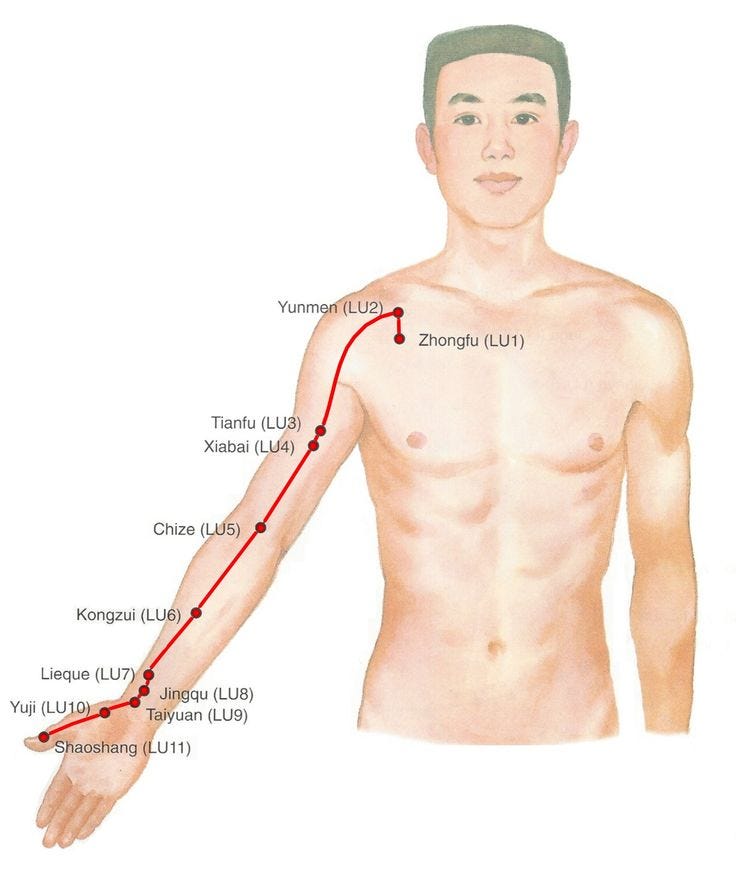

Let us unpack that. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) believes that in our bodies are channels called “meridians” through which “qi” (气), that is, air or energy, circulates. When these meridians are blocked, there is disease, and when they are clear, there is health.

Most Traditional Chinese Medicine therapies, such as acupuncture, acupressure, massage, gua-sha, moxibustion, and cupping, aim to clear the meridians to support the body's innate ability to self-regulate.

As a side note, it is interesting to remark that Ayurveda and Egyptian medicine, the other two oldest recorded medical traditions, also share similar theories.

According to Ayurveda, prana (breath, life force) circulates through the nadis (rivers), the obstruction of which is associated with disease and the release of which is associated with health. Along these nadis, points of special importance are called marmas.

According to ancient medical papyri, physicians in ancient Egypt viewed the human body through their theory of "channels" that carried air, water, and blood to the body. Like the Nile, whose blockage made crops unhealthy, obstructions along the channels were associated with disease, and a physician's job was to unblock them. A common greeting in ancient Egypt was, "May your channels be well”.

According to Kenneth M. Sancier, Ph.D., founder of the Qigong Institute in California,

One may speculate that an increase in blood circulation may help to explain the effect of qigong exercises on many different functions of the body. Increased blood circulation enhances delivery of oxygen and nutrients to cells of the body and increases the efficient removal of waste products from the cells. These processes may help nourish diseased or stressed tissue, increasing the efficiency of body functions including immune response, finally enabling the body to heal itself.

I find it interesting to notice that,

in Traditional Chinese Medicine, the word qi (气) refers to both the air we breathe and our life force,

in Ayurveda, the word prana (प्राण) also refers to both the air and our life force, and that,

according to Western biology, oxygen (O2) is needed to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the “energy currency” that all of our cells use to power almost all of their processes.

I am not a doctor (just a high school dropout 😆), but it seems to me that within the theoretical framework of modern medical science, it is not inconceivable that an intervention that increases circulation throughout the body, such as the Arms Swinging exercise, by improving cellular oxygenation, would support the smooth functioning of nearly all cellular processes and provide a myriad of physiological benefits.

But how does the Arms Swinging exercise compare to any other whole body movement?

I would love it if researchers could test this by comparing a 10-minute Arms Swinging group with, say, a 10-minute walking group.

Personally, I get more out of 10 minutes of Arms Swinging than I do out of 10 minutes of walking, and I believe there is more to the Arms Swinging exercise than just increased circulation.

I'll explain why in a moment, but first let us zoom out of our Arms Swinging / Ping Shuai Gong and learn more from the broader family of Qi Gong exercises.

Qi Gong

Qi Gong is an ancient Chinese system of health exercises characterized by gentle movements and mindfulness.

A systematic review published in 2020 titled Benefits of Qigong as an Integrative and Complementary Practice for Health, concludes that “the practice of qigong produces positive results on health” and can improve “numerous health conditions, such as: cancer; fibromyalgia; Parkinson’s disease; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; burnout; stress; social isolation; chronic low back pain; cervical pain; buzz; osteoarthritis; fatigue; depression; and cardiovascular diseases.”

Of course, no one is claiming that qigong “systematically cures” all of these diseases, only that it can improve them, with a degree of improvement that varies from person to person.

Also in 2020, Karen van Dam from the Faculty of Psychology of the Open University of the Netherlands published a review paper entitled Individual Stress Prevention Through Qigong. Here are interesting excerpts, first from its intro:

Over the past decades, stress has become an urgent health issue affecting individuals, organizations, and society.

[…]

Chronic overactivation can instigate a negative spiral in which an overloaded mind and body can diminish individuals’ ability to “switch-off” at night, thus lowering sleep quality and increasing exhaustion. Moreover, stress sensitization can develop, causing overactivated individuals to overreact to stressful situations and even create new stress situations, as stressed people might be less able to deal with situations adequately.

About the physiology of stress:

To meet the demands on and off work, the body reacts with the activation of a fast sympathetic system and a hormonal system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. In the first, rapid response, the hypothalamus sends a signal to the adrenal glands triggering the release of catecholamines, including the hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline. These hormones immediately activate the sympathetic nervous system, causing (among others) the heart rate to increase in frequency and contraction force, the blood to transport more oxygen, glucose, and fatty acids, increased muscle tension, and suppression of parasympathetic system activities, such as the immune system. At the same time, a hormonal system, the HPA axis, is activated in which the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary gland, through the corticotrope-releasing hormone (CRH) to produce the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then triggers the adrenal cortex to secrete cortisol. Cortisol supports the activities of the catecholamines by contributing to energy mobilization through increased glucose availability and by suppressing the highly demanding metabolic processes of the immune system, resulting in further availability of glucose. This second, HPA response develops a little slower than the first, neural response but then becomes the dominant response, especially in chronic stress and activation situations. The HPA axis plays a central role in regulating a large number of homeostatic systems in the body, including the metabolic system, cardiovascular system, immune system, reproductive system, and central nervous system.

We’ve already suggested that the increase in circulation throughout the whole body is an important therapeutic mechanism of action at work in the Arms Swinging. Here are others that we know of from the broader qi gong family that I think it is reasonable to attribute by inference to the Arms Swinging:

During Qigong, practitioners’ attention is focused on the movements, body positions, and breathing pattern. This focused attention creates an awareness-in-the-moment (mindfulness) in which past and future are disregarded. For this reason, Qigong is also referred to as “meditation in motion” and “meditative movement”. An important outcome of Qigong is therefore a state of mental peace, or “rujing”. […]

Findings indicate that practicing Qigong can provide benefits to stressed and overactivated workers, improving their physical and psychological well-being. […]

Increased heart rate variability* was found after a 12-week program of one-hour Qigong training three times a week, suggesting increased parasympathetic activity**.

* Heart rate variability (HRV) is the variation in the time interval between heartbeats. Low HRV is associated with stress and poor health, while high HRV correlates with low stress and good health.

** Our parasympathetic nervous system is our rest and repair, "long-term happiness" mode.

If you remember the little Arms Swinging survey I presented at the beginning, most practitioners also report an increase in mindfulness and inner calm.

I would like to suggest that in the Arms Swinging exercise, the mental counting and repetitive nature of the movement provides additional support for the Relaxation Response.

The Relaxation Response is a concept coined in the 1960s by Dr. Herbert Benson, the cardiologist and researcher who founded Harvard's Mind/Body Medical Institute.

The Relaxation Response is the opposite of the fight-or-flight response, and Dr. Benson says it can be consciously induced through

gentle focus, and,

repetition.

When practicing the Arms Swinging, we

mentally count "1 and 2 ... 3 ... 4 ..." while focusing on our body, and

swing our arms repeatedly.

One way neuroscience can shed light on the Relaxation Response is that focusing in the present moment quiets the Default Mode Network, the neural network that is responsible for discursive thinking about the past and the future and for self-referential worry. Simply put, focusing on the present moment gives us a welcome break from the "voice in our head”. Repetition then allows for predictability, an important cue for our brain to decrease activity in the sympathetic nervous system, our short-term survival mode, and increase activity in the parasympathetic nervous system, our long-term happiness mode. With increased parasympathetic activity, our metabolism, heart rate, respiratory rate, and brain waves all slow down: we are more relaxed and we can think more clearly.

Ping Shuai Gong instructors also describe this Relaxation Response in their own terms:

Even and rhythmic swings enhance the circulation of qi and blood. Once your body establishes a comfortable rhythm, it reaches a dynamic stability, putting your mind in a naturally focused state. The ultimate form of mental focus is a wonderful state of peacefulness and serenity.

The review paper continues:

Practicing Qigong also appears to support the respiratory system as it increases lung capacity, oxygen intake and improves breathing patterns.

This is also true for the Arms Swinging exercise. After practicing just 10 minutes every night for a week, 75% of the participants reported an improvement in their breathing quality. One participant shared Arms Swinging with her sister, who has asthma, and she also noticed a positive difference.

From a TCM perspective, swinging our arms increases circulation along the lung meridian.

From the Ping Shuai Gong booklet:

During the exercise, when qi fills up your fingers, it will begin to resonate with and circulate throughout your internal organs, which will gradually recuperate.

This is because the fingers and toes are the ends of the twelve primary meridians, and energy reaching them is a sign that the meridians are clearing. When our meridians are clearer, qi flows better, nourishing and improving the function of the organs.

Swinging our arms well parallel to each other also gently massages the erector spinae, the group of muscles and tendons that run along both sides of the spine and are responsible for straightening and rotating the back.

From a TCM perspective, this promotes circulation along the back shu (俞) points, an important series of twelve points that correspond to the twelve major organs in our body (see zang-fu theory). The highest of these points is fei-shu (肺俞), known in English as "lung shu", and is one of the most important point for all lung-related issues.

Here are more insights from our review paper on qi gong and mental health:

Stress levels

Practicing Qigong is associated with a reduction in both perceived stress and hormone levels (adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol). Studying a group of computer operators, Skoglund and Jansson found that Qigong reduced noradrenaline excretion in urine and influenced the heart rate and temperature, indicating decreased activity of the sympathetic nervous system. Together, these findings suggest that Qigong has an inhibitory effect on the stress response.Sleep quality and fatigue

Qigong leads to improved sleep quality and a reduction in fatigue and exhaustion complaints, which are important indicators of burnout. At the end of a nine-week intervention program with two one-hour Qigong training sessions a week, participants reported improved sleep quality and sleep latency (i.e., the time to fall asleep) and less fatigue than before the intervention; this effect was still noticeable after three months.Anxiety

Meta-analytic review studies suggest beneficial effects of Qigong on both momentary (i.e., state) anxiety and chronic (i.e., trait) anxiety. Johansson and colleagues observed an immediate effect of a single Qigong training on state anxiety. Chow et al. found a long-term effect of an eight-week Qigong training program on participants’ anxiety levels.Depression

Findings indicate that Qigong can alleviate depressive complaints. Chan et al. reported a reduction in depressive symptoms immediately and three months after a 16-week Qigong intervention. A 10-week Qigong training for nursery and midwifery students resulted in reduced depressive mood. The effectiveness of Qigong in relieving depression has been attributed to a reduction in cortisol levels and activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.Cognitive functioning

Because Qigong is associated with focused attention and a reduced stress response, it may also provide cognitive benefits. A study with healthy, older adults showed that the practice of Qigong was related to an improvement in cognitive functioning that was maintained over a 12-month period. Ladawan and colleagues similarly found that Qigong exercise improved cognitive functioning (attention, brain processing speed, and maximum workload) of healthy practitioners. However, this effect disappeared 12 weeks after discontinuation of Qigong, which suggests that performing Qigong regularly is an important condition for maintaining an effect.

Regularity is key, and the key to regularity is small daily habits, which is why I recommend 10 minutes of Arms Swinging every night before bed.

As Qigong lowers practitioners’ stress and activation levels, people might be better able to distance themselves from a situation, appraise it more positively, and generally show improved emotion regulation. Following, they will experience less mental stress, and their responses to situations will be less intense. In this way, Qigong practice may contribute to a positive spiral that enhances individuals’ well-being.

The paper then suggests another mechanism of action:

Research also shows that it matters whether one breathes through the nose, as is common practice in Qigong, or through the mouth. When inhaling through the nose, neurons in the limbic system (especially the amygdala, hippocampus, and olfactory cortex) are stimulated; these are brain areas where emotions, memory, and scents are processed. Subjects in Zelano et al.’s study who were breathing through the nose performed better on memory tasks and responded less strongly to emotional stimuli than subjects who were breathing through the mouth.

Nasal breathing is something I stress over and over again, not just while Arms Swinging but throughout the day. In addition to what the article mentions, we can add that our nose filters, warms, and humidifies the air. It slows down our respiratory rate, which contributes to soothing our nervous system. Nasal breathing also produces nitric oxide, an important vasodilator which improves oxygen circulation and absorption.

I would like to suggest that the gentle smile I recommend during Arms Swinging also contributes to the increase in mindfulness and relaxation.

In their 1993 scientific paper “Voluntary Smiling Changes Regional Brain Activity”, psychology professors Paul Ekman (UCSF) and Richard J Davidson (University of Wisconsin-Madison) report:

Our finding that voluntarily making two different kinds of smiles generated the same two patterns of regional brain activity as was found when these smiles occur involuntarily suggests that it is possible to generate deliberately some of the physiological change which occurs during spontaneous positive affect. […] While emotions are generally experienced as happening to the individual, our results suggest it may be possible for an individual to choose when to generate some of the physiological changes that occur during a spontaneous emotion - by simply making a facial expression.

In 2012, psychologists Tara Kraft and Sarah Pressman of the University of Kansas published a clever study in the journal Psychological Science on the effect of voluntary smiling on stress. The 170 participants, who were unaware of the true purpose of the study, were asked to hold chopsticks in their mouths in a way that produced either,

a neutral expression,

a smile with lips only, or,

a full smile with lips and eyes, the famous Duchenne smile.

The participants were then asked to perform two cognitively demanding tasks.

Findings revealed that all smiling participants, regardless of whether they were aware of smiling, had lower heart rates during stress recovery than the neutral group did, with a slight advantage for those with Duchenne smiles. Participants in the smiling groups who were not explicitly asked to smile reported less of a decrease in positive affect during a stressful task than did the neutral group. These findings show that there are both physiological and psychological benefits from maintaining positive facial expressions during stress.

A 2019 meta-analysis of facial feedback research combined data from 138 studies from around the world, involving more than 11,000 participants. Interestingly, the paper begins and ends with a critical approach to a famous quote from my teacher, the late Zen master Thích Nhất Hạnh: "Sometimes your joy is the source of your smile, but sometimes your smile can be the source of your joy.”

The nature of scientific inference prevents us from concluding that “your smile can be the source of your joy” with anywhere near the confidence that Thích Nhất Hạnh could. Besides, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s concept of joy is probably a rare commodity in most psychology laboratories.* Nonetheless, a half century’s worth of experimental findings does provide considerable evidence that smiles, frowns, scowls, and other facial movements can affect emotional experience in a variety of scenarios. At the same time, our meta-analysis indicates that the effects are quite small and appear to vary for reasons that our meta-analysis did not shed light on.

* 😅

Context is important, and I agree with Nicholas A Coles, the lead researcher on this study, when, in an interview, he relativizes,

A lot of people think that you can smile your way to happiness, but these effects don’t really seem to be that powerful.

Happiness is multifactorial, and we need a complete happiness toolbox for our lives. Still, one of these tools is a voluntary, gentle Duchenne smile, when it feels kind and appropriate, because such a smile can make us a little more relaxed and resilient.

I will give more practical advice on how to smile in our next article.

Standing on our toes and putting our heels back down to the ground, as we do in the Arms Swinging, is a common Qi Gong move. For example, it is the last exercise in the Eight Pieces of Brocade (ba-duan-jin, 八段錦), one of the most popular series of qi gong exercises in the world, and is called “Bouncing Seven Times on the Toes to Prevent a Hundred Diseases” (背后七颠百病消).

This is how the Shaolin Temple Overseas Headquarters explains this exercise:

According to Chinese medicine, the toe is the contact point of the “leg san yang” meridian and the “leg san yin” meridian. When the ten toes grip the floor, this stimulates the six yin and six yang meridians.

We said earlier that the extremities are the end of the twelve primary meridians. “San” means “three”. A "yin" meridian is a meridian located primarily on the inner part of a limb, while a "yang" meridian is a meridian located primarily on the outer part of a limb.

Note that each meridian is present symmetrically on the left and right sides of the body. I suppose this is why the article counts twelve meridians stimulated by standing on our toes.

This causes the qi and blood to be regulated and improves the function of corresponding internal organs.

Same mechanism we saw earlier: extremities filled with qi = clear meridian = nourished organ = improved function.

The article then suggests another mechanism of action:

Furthermore, bouncing on the feet can stimulate the “du mai” (du meridian), adjust the balance of the body’s yin and yang and promote health and rehabilitation.

The du-mai meridian, or Governing Vessel, begins at the tailbone, runs up through the spine to the top of the head, then down the forehead and nose to end at the upper lip area:

The du mai is closely connected to the brain, spinal cord and kidney. “Du” literally means a commander, which governs a whole system. The du mai passes through the back and makes contact with the yang meridians of the hands and feet. It has the function of governing and balancing qi of the whole body’s yang meridians. Therefore, people refer to it as a commander and regulator of the yang. […] In this bouncing feet motion, the power passes up starting from the heel, to the joints, and passes up to the spine then to the brain. This movement makes the spine shake slightly and stimulates the body’s central nervous system.

Most of us in our day and age,

think too much,

spend too much time on electronic devices,

do not walk enough, and,

lock our feet in shoes.

Our energy is too high in our heads and our feet are under stimulated.

Standing on our toes and putting our heels back on the ground, as we do between the first and second counts of the Arms Swinging, activates the large number of sensory receptors and nerves in our ankles and feet that play a crucial role in regulating balance and stability.

Our energy goes down, we feel more grounded, and we can wind down before bed.

In my little survey, most participants report that practicing 10 minutes of Arms Swinging before bed helps them sleep better.

We can surmise that this improvement in sleep quality is due to,

the Relaxation Response — which we know helps with sleep,

the toe rising motion — which brings our energy down in a similar way to foot bath and foot massage which we know also help with sleep, and

the routine component — some practitioners make it a point to do their Arms Swinging early enough and go to bed right after.

In the words of Matthew Walker, PhD, author of Why We Sleep,

If sleep didn't serve an absolutely vital function, it would have been the biggest mistake our evolutionary process ever made. We're not reproducing, we're not gathering food, we're not socializing, and worse... we're very vulnerable to being attacked.

But evolution didn't make any mistake. Every physiological system in the body and every single operation of the mind is wonderfully enhanced by sleep when you get it, and demonstrably impaired when you don't get enough. Sleep is a remarkable investment.

The quality of our sleep affects everything from our immunity and mood to our cognitive function and even our longevity, and it seems safe to me to count improved sleep not only as a benefit of the Arms Swinging but also as another of its therapeutic mechanisms of action.

Another very exciting therapeutic potential of the Arms Swinging is the relief of all kinds of physical pain.

One in five adults in the United States and Europe suffers from chronic pain, defined as pain that lasts more than three months and occurs on most days, with the most common sites of pain being the back, hip, knee and foot. Physical pain is a serious impediment to people's quality of life, affecting their mental health, daily activities and participation in society. While most people with chronic pain still prefer physical therapy and massage, many also turn to prescription and illegal drugs, and the desperate search for pain relief, coupled with the predatory behavior of the financial-pharmaceutical industrial complex, has enabled the emergence of our recent tragic opioid crisis.

I believe self-care education can provide individuals with safe, significant, and lasting pain relief, at low cost if delivered in person, and even at no cost if delivered online.

Practitioners of Arms Swinging often report improvements in pain levels, typically within less than a week of practicing 10 minutes each night before bed. The analgesic benefits of Arms Swinging can be explained by the four main mechanisms of action we've proposed in this article: increased circulation, relaxation response, improved breathing, and increased mindfulness.

Increased Circulation

Swinging our arms,

loosens our wrists, elbows, and shoulders,

softens the fascia in our arms and back, and,

promotes blood and lymph circulation throughout our upper body.

Bending our knees,

loosens our ankles, knees, and hips,

softens the fascia in our legs and lower back, and,

promotes blood and lymph circulation throughout our lower body.

According to a TCM saying, "痛則不通, 通則不痛" — "Pain is a blockage, a lack of circulation. Restore the circulation and the pain goes away." However, care must be taken to restore circulation safely. During the healing phase, and especially in a body that is misaligned and tense, it is preferable to promote circulation without muscle contraction. This is what Arms Swinging does.

Relaxation Response

In 2021, a Norwegian team of researchers conducted a systematic review of randomized controlled trials on the analgesic effects of relaxation techniques. They did not include studies on mindfulness because although “there are some overlaps between mindfulness and relaxation techniques”, “they have different agendas. Relaxation techniques aim to reduce stress and tension, while the purpose of mindfulness is to observe and accept these feelings.”

Twenty-one studies found significant improvement in pain.

Four studies showed improvement in secondary outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, well-being and coping strategies.

Four studies showed no significant improvement.

Unfortunately, their exploration of potential mechanisms of action is quite shallow, but here are a few:

Relaxation techniques have several detectable physiological effects, for example lower cortisol levels and inhibition of inflammatory processes.

Cortisol and inflammation are both correlated with pain.

One possibility is that relaxation techniques reduce chronic pain through triggering pain inhibitory processes in the brain, which further influence the pain experience. According to the neuromatrix theory, pain signals to the brain are inhibited by relaxation because the amount of pain signals to the brain are reduced.

The history of pain theories is fascinating and I hope to be able to learn more about it in the future. The neuromatrix theory of pain, introduced by Dr. Ronald Melzack in the 1990s, states that "the perception of painful stimuli does not result from the brain's passive registration of tissue trauma” (as the “direct-line theory of pain” previously proposed), “but from its active generation of subjective experiences through a network of neurons known as the neuromatrix”.

By producing a Relaxation Response, the authors suggest, one is able to positively affect one’s neuromatrix and thus lower one’s experience of pain.

Relaxation is considered one of the most available and cost-effective treatments for chronic pain. Also, there are no known side effects.

Improved Breathing

By “improved breathing” I mean a breathing that is,

nasal,

slower — ideally about 6 breaths per minute,

deeper — “diaphragmatic” or “abdominal”,

more regular,

quieter, and,

more enjoyable.

A European study published in 2020 in the Journal of Pain reports,

Slow deep breathing (SDB) is commonly employed in the management of pain, but the underlying mechanisms remain equivocal. This study sought to investigate effects of instructed breathing patterns on experimental heat pain and to explore possible mechanisms of action. In a within-subject experimental design, healthy volunteers (n = 48) performed 4 breathing patterns: 1) unpaced breathing, 2) paced breathing (PB) at the participant’s spontaneous breathing frequency, 3) SDB at 6 breaths per minute with a high inspiration/expiration ratio (SDB-H), and 4) SDB at 6 breaths per minute with a low inspiration/expiration ratio (SDB-L). During presentation of each breathing pattern, participants received painful heat stimuli of 3 different temperatures and rated each stimulus on pain intensity. Respiration, heart rate, and blood pressure were recorded. Compared to unpaced breathing, participants reported less intense pain during each of the 3 instructed breathing patterns. Among the instructed breathing patterns, pain did not differ between PB and SDB-H, and SDB-L attenuated pain more than the PB and SDB-H patterns. The latter effect was paralleled by greater blood pressure variability and baroreflex effectiveness index during SDB-L. Cardiovascular changes did not mediate the observed effects of breathing patterns on pain. […] Slow deep breathing is more efficacious to attenuate pain when breathing is paced at a slow rhythm with an expiration that is long relative to inspiration, but the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

This is not surprising, since the inhalation is associated with sympathetic activity and the exhalation with parasympathetic activity.

In 2012 (n=16) and 2009 (n=20), other university researchers induced thermal pain in their (innocent) undergraduate students while instructing them to breathe slowly. Both studies found that a slower, deeper breathing provided analgesic benefits, with the 2009 study suggesting that this has to do with the increased vagal cardiac activity:

Because respiration is also known to produce robust changes in cardiac activity, (i.e., respiratory sinus arrhythmia, RSA), it is thought that a common biological process may explain both respiratory-induced analgesia and respiratory-induced changes in cardiac activity. Respiratory-induced changes in cardiac activity are mediated by a complex pattern of physiological responses, including variations in pulmonary volume, arterial blood pressure (BP), as well as baroreflex, brainstem, and vagal cardiac activity. These responses: 1) are relatively rapid; 2) help buffer changes in blood pressure; and 3) are thought to trigger pain inhibition. Breathing-induced analgesia, therefore, should be strongest when breathing-induced changes in heart rate (HR) are largest. Concurrently recording HR and pain sensitivity should help validate this hypothesis and should increase our general understanding of the mechanisms underlying breathing-induced analgesia. […]

Our findings, therefore, corroborate anecdotal reports that suggest that slow deep breathing yields analgesic effects. We initially hypothesized that a common biological process might explain breathing-induced analgesia and breathing-induced changes in HR. In support of this hypothesis, we found that slow deep breathing and HR biofeedback produced the largest decrease in pain sensitivity, while also producing the largest variability in HR (SDNN). A rise in peak-to-valley amplitude (indices of vagal activity) during slow deep breathing and HR biofeedback supports the idea that slow breathing (at about 6 breaths/minute) increases vagal activity. Furthermore, frequency domain analyses of the ECG output revealed a sharp increase in LF power during slow deep breathing and HR bio- feedback. This rise naturally occurs when breathing slows down and happens because the oscillations associated with RSA (which are usually expressed in the HF component) overlap with the slow HR oscillations (LF component). This phenomenon is directly tied to breathing oscillations and also indexes vagal cardiac activity. […] We believe that the analgesia produced during slow deep breathing was not entirely caused by distraction effects, as slow deep breathing produced a greater increase (from baseline) in pain tolerance than the distraction condition. […] Slow deep breathing is a simple and easy to use method to relieve acute pain that could easily be used for painful medical procedures (shots, punctures, dressing change, childbirth, etc.), to help alleviate acute painful crisis or as a complementary pain treatment for chronic pain.

A systematic review entitled Pain and Respiration sheds further light on potential mechanisms of action,

The literature describes an inverse correlation between BP levels and pain sensitivity. Such an association may be functional in that it works to reduce the impact of pain in stressful and threatening situations. Several mechanisms have been proposed for the association, including stimulation of baroreceptors, lowering cerebral arousal, or endogenous opioids and noradrenergic pathways as a crucial component of descending inhibitory activity. […] Although direct central mechanisms could also play critical roles in the integration of pain and breathing, the baroreceptor system seems to play an essential role in the relationship between cardiovascular, respiratory activity, and pain dampening through the cardiovascular or central branch of the system.

According to a study published in the Journal of Korean Society of Physical Therapy, another mechanism of action of slow diaphragmatic breathing for low back pain (the most common type of musculoskeletal complaint), is biomechanical: the movement of the diaphragm gently stimulates the external obliques and lumbar muscles, keeping them relaxed and active, thereby reducing pain.

Increased Mindfulness

My experience of occasionally doing Arms Swinging while having a conversation (😆) leads me to believe that the therapeutic effects of Arms Swinging are mostly mechanical. As long as we do the movements correctly, we get most of the benefits, whether we are mindful or not. That said, the gentle nature of the exercise, coupled with the counting, naturally invites mindfulness, i.e., non-discriminatory attention, a healthier mental attitude toward physical sensations which can provide further relief.

This is how the Buddha taught his disciples:

Meditate on sensations as they are, keen, aware, and mindful, having overcome all desire and aversion.

A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of mindfulness meditation for chronic pain reports,

Thirty-eight RCTs met inclusion criteria; seven reported on safety. We found low-quality evidence that mindfulness meditation is associated with a small decrease in pain compared with all types of controls in 30 RCTs.

In their book Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body, science journalist Daniel Goleman and neuroscientist Richard Davidson write,

For the yogis, their pain matrix showed little change in activity when the plate warmed a bit, even though this cue meant extreme pain was ten seconds away. Their brains seemed to simply register that cue with no particular reaction. But during the actual moments of intense heat the yogis had a surprising heightened response, mainly in the sensory areas that receive the granular feel of a stimulus—the tingling, pressure, high heat, and other raw sensations on the skin of the wrist where the hot plate rested. The emotional regions of the pain matrix activated a bit, but not as much as the sensory circuitry. This suggests a lessening of the psychological component—like the worry we feel in anticipation of pain—along with intensification of the pain sensations themselves. Right after the heat stopped, all the regions of the pain matrix rapidly returned down to their levels before the pain cue, far more quickly than was the case for the controls. For these highly advanced meditators, the recovery from pain was almost as though nothing much had happened at all. This inverted V-shaped pattern, with little reaction during anticipation of a painful event, followed by a surge of intensity at the actual moment, then swift recovery from it, can be highly adaptive. This lets us be fully responsive to a challenge as it happens, without letting our emotional reactions interfere before or afterward, when they are no longer useful. This seems an optimal pattern of emotion regulation.

In summary, mindfulness reduces,

pre-stimulus anticipation,

intra-stimulus resistance, and,

post-stimulus rumination,

the three components of what psychologists call “pain catastrophizing”.

One metaphor the Buddha used to describe how unpleasant events affect highly mindful people is that of drawing a line on water.

Interestingly, the Buddha also taught that enlightenment, the ultimate goal of mindfulness practice, is to permanently rewrite our nervous system's response to physical sensations:

The underlying tendency to seek pleasant sensations should be released. The underlying tendency to shun unpleasant sensations should be released. The underlying tendency to ignore neutral sensations should be released.

The goal is to enjoy a completely open and undivided mind that allows all physical sensations to come and go naturally. In this way,

When a learned noble disciple experiences painful physical feelings they don’t sorrow […]. They experience one feeling: physical, not mental.

To be clear, I am not claiming that Arms Swinging miraculously cures all pain, but simply that,

many Arms Swinging practitioners report significant pain relief,

there are plausible mechanisms of action, and therefore,

the exercise deserves serious exploration.

If you have chronic pain and are interested in the Arms Swinging exercise but have physical limitations that prevent you from doing it fully, in my next newsletter I will show you how you can adapt it to your current mobility.

The review paper on Qi Gong and stress prevention concludes:

Studies with RCTs have shown that practicing Qigong impacts the effects of stress and overactivation by decreasing stress levels, hypertension, depression, and anxiety, and improving the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, immune function, sleep quality, cognitive functioning, and stress appraisal.

[…]

Extensive empirical evidence suggests that Qigong provides an effective means for individual stress prevention that individuals can use to recover from stress and sustained activation, regain homeostasis and mind–body balance, and improve their physical and psychological well-being.

People who are used to thinking in terms of "one pill, one disease" are surprised to learn about the wide range of benefits of Qi Gong and other lifestyle interventions. The reason Qi Gong can help with such a wide variety of ailments is because it supports our innate self-regulating and self-repairing processes. A Qi Gong practitioner is not "fighting disease" but rather, as Taoists see it, "nourishing life" (yang sheng, 养生).

Practicing the Arms Swinging exercise is a gentle way to take care of ourselves that can positively affect many systems in our body and mind. If you’re familiar with my work, you will recognize this is the 5th DWEP Criterion — “holistic effectiveness”.

Summary

Although it is a deceptively simple exercise that takes only 10 minutes, my experience and the feedback of many practitioners leads me to believe that the Arms Swinging has tremendous therapeutic potential for physical and mental health.

Scientific research on its closest sibling Ping Shuai Gong and the broader family of Qi Gong exercises can provide a theoretical framework to envisage four main mechanisms of action:

I would like to work with researchers to learn more about the experiences of Arms Swinging practitioners, using both subjective and objective measures. If you can help conduct such a study, please contact me.

In the end, the only thing that really matters is what this exercise can do for you. And there is only one way to find out: give this exercise a serious try by practicing it for 10 minutes every night for a month. Watch the video several times, especially in the beginning, because the details really matter.

In our next and final article in this series on Arms Swinging, I will give more practical advice.

Until then, "May your channels be well”.

🙏💛

This newsletter is free and will remain free. It is 100% written by me. I only use AI to help me with the spelling, grammar, and word use. I welcome concrete and specific suggestions for improvement.

The #1 thing you can do to get started on this Mental Health Revolution is to print a Daily Wellness Empowerment Program (DWEP) Sheet and get going.